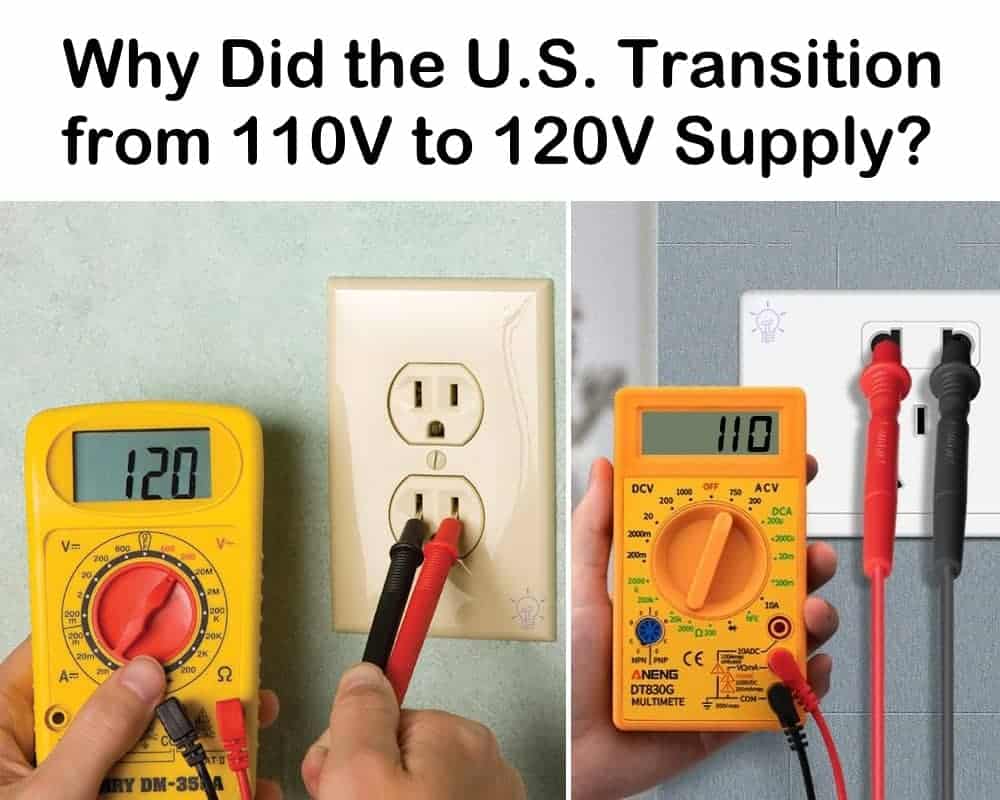

When and Why Did the U.S. Transition from 110V to 120V Supply?

Why Did the Voltage Level Increased from 110V to 120V in North America?

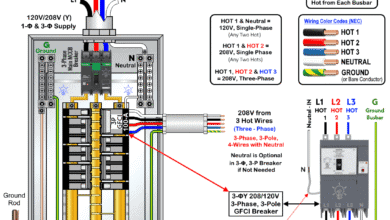

Electric power transmission and distribution is not as straightforward in the U.S. as it is in IEC-following countries. For instance, most of these countries including the UK, Australia, and many European and Asian nations (except Japan) use 230V for single-phase and 400/415V for three-phase applications. In contrast, the U.S. employs multiple voltage levels for both commercial and residential applications, such as 120V (previous 110V), 208V, 240V, 277V, and 480V. Canada, which shares similarities with the U.S. and has smelteries in North America, also offers different voltage levels like 347V and 600V.

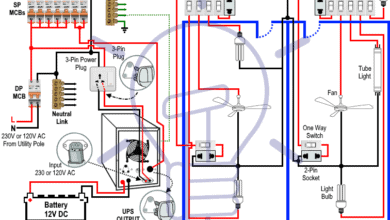

First of all, let’s clarify that electrical panels in residential premises do not supply only 110V; they also provide a 240V single-phase supply, similar to the 230V supply used in IEC-compliant countries. The difference is that 120V is available between a phase (hot) wire and neutral for small-load applications. On the other hand, 240V is available between two hot wires (Phase 1 and Phase 2) for heavy-load appliances such as dryers, stoves, and electric heaters.

About a century ago, the standard voltage in the U.S. was 110V, but over time it gradually increased to 120V (±5%). This means you may observe slightly lower or higher voltage at an outlet or main panel due to the permissible voltage drop variation.

Originally, 110V was common in the 1920s. This increased to 115V during the 1930s, then to 117V in the 1950s, which was briefly adopted as the standard. However, it was soon replaced by 120V in the 1960s, which remains the standard today.

During the War of Currents between AC and DC, it is possible that Thomas Edison initially chose 110V so that approximately 100V could be delivered at the socket outlet, compensating for the significant voltage drop in wiring conductors. At the time, electrical insulation and safety measures weren’t as advanced as they are today. Lower voltage meant a reduced risk of electrocution and other electrical hazards. At 100V, incandescent bulbs operated effectively without burning out too quickly. This may also be one reason why Japan adopted 100V as its standard voltage.

In the 1930s, as the reliability and lifespan of light bulbs improved and electric motors became more common, power suppliers increased voltage levels from 110V/220V to 115V/230V. Eventually, when equipment and infrastructure were upgraded, the National Electrical Code (NEC) standardized the voltage in North America to 120V and 240V.

Some older devices and plugs from various manufacturers are still rated for and can operate at 110V or 115V, as they are compatible with the lower end of the voltage range. Conversely, you may encounter ratings such as 125V/250V on certain appliances and outlets (such as NEMA 120V/240V receptacles) which indicate the maximum operating voltage they can safely handle. The shifting process was easy as many appliances and devices were already designed to operate on 110-120V, making the 120V standard convenient for consumers and manufacturers.

Despite the change, some people continue to refer to the system as “110/220,” a habit that lingers from earlier standards. A similar case can be seen in regions using 230V today, where many still refer to it as 220V, even though the change from 220V to 230V was officially implemented in 1989.

- Related Post: Why Does Japan Use 100V as the Standard Voltage?

When and Why Did They Changed from 110V to 120V?

The U.S. residential power supply didn’t transition from 110V to 120V in a single, sudden shift, but rather through a gradual evolution driven by practical considerations and standardization efforts.

The United States transitioned from a nominal 110V to a 120V standard for residential and commercial use primarily due to safety, convenience, and practicality considerations in the 1920s. The shift also reflected the evolving landscape of electricity distribution and the increasing popularity of AC power.

When the Transition Occurred:

Thomas Edison’s early (late 19th/early 20th century) DC distribution systems were initially around 110V. When AC power began to prevail championed by George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla due to the use of transformer to easily increase and decrease the level of voltage. Finally, It was standardized around 110V to ensure compatibility with existing incandescent light bulbs.

Over the years, the nominal voltage gradually increases from 110V up to 117V. You can find appliances from the 1940s and 50s labeled 110V, 115V, or 117V.

Final Standardization occurred in the 1960s/1970s. The current standard of 120/240V at 60 Hz was largely solidified around 1967 and further reinforced by the National Electrical Code (NEC) changes in 1968 and 1984. By the early 1970s, the electrical industry formally raised the voltage to 120/240 volts from 110/220 volts.

Why the Transition Occurred:

The gradual increase from 110V to 120V and its standardization were due to the following reasons:

Early incandescent light bulbs, which were a major load in the early days of electricity, performed optimally in terms of brightness and filament life within a certain voltage range. As filament technology improved, they could reliably handle slightly higher voltages, leading to the shift.

As more and more appliances were introduced into homes, and electricity consumption increased, a slightly higher voltage allowed for more power to be delivered without needing significantly larger (and more expensive) wire sizes. Higher voltages allow for smaller wire sizes for the same power (watts) since:

P = V × I.

Another reason for increase to cranked up the to regulating voltage on the power distribution and transmission transformers. Similarly, when more motor circuits were added in the residential and commercial applications, the National Electrical Code (NEC) eventually updated motor ratings to reflect the 120V standard, reflecting the industry’s shift.

In term of reduces line losses, a slightly higher voltage (like 120V instead of 110V) for the same power (watts) means lower current (Amps). Since heat losses in conductors are proportional to the square of the current (I2R), a lower current reduces energy loss in the wiring. While the jump from 110V to 120V is small, it contributes to overall system efficiency.

Finally, it was the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) who played a role in establishing 120V in 1920s as the standard. This standardization was key rule for manufacturers to produce appliances with compatibility that would work reliably across the country, and for electricians to wire homes consistently.

Related Posts:

- Standard Voltage (V) and Frequencies (Hz) Around the World

- Why Does Japan Use Both 50Hz and 60Hz in Its Power System?

- Which Transformer is More Efficient When Operates on 50Hz or 60Hz?

- Can We Operate a 60Hz Transformer on 50Hz Supply Source and Vice Versa?

- Difference between AC and DC (Current & Voltage)

- Difference Between 120V and 240V/230V AC Power Supply

- AC or DC & Which One is More Dangerous And Why?

- Which One is More Dangerous? 120V or 230V and Why?

- Which One is More Dangerous? 50Hz or 60Hz in 120V/230V & Why?

The author of the article couldn’t be more wrong in his assumption or statements.

The standard distributed voltages are set deliberately above the utilization equipment and appliance voltages agreed to by the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE). The NEC had nothing to due with it. Our voltages went up because NEMA agreed that low voltage utilization equipment would be rated and operate at 115, 230, 460, and 575, plus or minus 10 percent. Utilities generate and distribute higher voltages to account for line losses and voltage drop at the consumptive devices. North America is unique in that our split-phase is a modification of Edison’s 220 volt split-generator output with two 110 volt and one 220 volt output. The AC system was adapted to have a 240 volt split into two 120 volt “phases.” Most of the adaptations were complete before WWII but labels can still be found with 110, 220, 440, etc.

Line voltage can be anywhere from 105 to 130v depending on load on your section of grid, rural or city and other factors. That’s what is know as brown out when it drops low and why in rural areas if the voltage is high light bulbs don’t last.

My previous house line voltage was consistently 245 to 255 incoming ( so each leg was 125 +) . Bulbs didn’t last unless I ran 130v bulbs. But my power bill was low in cost

The U.S. transition from 110 volts to 120 volts AC occurred gradually over the 20th century, mainly from the 1920s through the 1960s and early 1970s. Originally, the standard residential voltage was about 110 volts, established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries during Thomas Edison’s early DC distribution systems. This nominal 110 volts was chosen partly because it allowed around 100 volts to be delivered at the socket, compensating for voltage drop in early wiring and improving safety with limited insulation technology at that time.

Over the decades, the voltage increased in stages:

– About 110V in the 1920s,

– Raised to 115V in the 1930s as light bulb and appliance technologies improved,

– Increased to roughly 117V by the 1950s,

– Finally standardized to 120V by the 1960s.

This change was driven by improvements in incandescent bulb durability and motor design, which allowed for slightly higher voltages without reducing lifespan. Higher voltage also reduced current for the same power, which decreased energy losses in wiring and enabled smaller, less costly conductors. The National Electrical Code (NEC) formally recognized 120/240 volts around 1967, with further reinforcement in 1968 and 1984, setting the modern U.S. residential voltage standard. The 120V supply comes from the voltage between a hot conductor and neutral, while the 240V supply used for heavy appliances is derived from connecting two hot conductors of opposite phases.

The shift was smooth because many electrical devices were already designed to work across a voltage range including 110 to 120V. The U.S. system remains unusual compared to the 230V standard used in most other countries, which stems from historical developments during the War of Currents and infrastructure choices made early on.

In summary, the U.S. moved from 110V to 120V to improve efficiency, safety, and compatibility with evolving electrical appliances, with the transition formalized mid-20th century through national standards and codes.

When alternating current (AC) systems took over (thanks to Tesla and Westinghouse), early systems tried to stay compatible with Edison’s existing 110V DC lighting loads.

Early AC generators were designed to output about 110–112 volts RMS.

Engineers realized over time that slightly increasing voltage reduced losses over long wire runs (a big issue as the grid expanded).

So utilities slowly raised it — first to 115V, then to 120V. The U.S. has been on the 120/240 split phase standard for homes since the 1960s.

True but reality is that ac voltage ranges from 114 to 125v ac. The utility won’t do anything unless the voltage falls outside those parameters! 42 years working for an electric utility!

Everyone is always looking for a conspiracy. It is caused by voltage drop in the circuit. It starts off 120-125VAC at the sub station and by the end of the circuit it is as low as 110VAC. Electrical appliances have a tolerance although resistive loads like incandescent light bulbs and space heaters will last longer on the low end and inductive loads such as refrigerators and AC units will last longer on the high end. Capacitive loads like electronics really don’t care much. You pay for the wattage not the voltage so your costs of operation are not affected much. A resistive load like a space heater will draw less amperage at lower voltage but will take longer to perform a task like heat up a room. A inductive load will fluctuate how much current it is drawing to output a predetermined wattage so if the voltage is higher the amperage is lower but the wattage stays more or less the same. A capacitive load is most likely electronically controlled to operate at a specific wattage and will adjust amperage accordingly. The whole 120, 115, 110 thing is all just a nominal voltage so tradesmen know which circuit you are talking about and are used interchangeably throughout the day.